A brief history of the CPI conventions

“Send three and fourpence – we’re going to a dance”

A brief history of the CPI conventions

1986 (1979) – 2013 (2024) - with anecdotes.

Click here for Appendix 1.

Click here for Appendix 2.

Prologue

The Construction Project Information committee (CPIc) was responsible for providing best practice guidance on the content, form and preparation of construction production information (CPI), and making sure this best practice was disseminated for take up throughout the UK built environment sector. It comprised the sponsoring bodies listed below at the time its operation ceased.

When and why did it cease operation after around 27 years of serving the sector?

There is no definitive date but a letter in August 2013 from the then RICS Chief Executive to the other sponsoring bodies records that the emphasis on Building Information Modelling (BIM) in the government's Construction Strategy in 2011 (aka ‘UK BIM initiative’), and the funding made available as a part of that, brought into focus that resource issues within CPIc had rendered it to be struggling at best to cope with the required massive and rapid ramping-up of the sector’s need for guidance on how to deal with the challenges. Prior to 2011 CPIc had been the only formally constituted multi disciplinary representational body working across the subject and that letter proposed absorbing the technical expertise of CPIc into the Construction Industry Council (CIC) which had significant sector and political influence and which by then had begun to discuss BIM. That did not happen.

That 2013 letter of itself is not hugely important in the story, it was discussed and responded to, but in hindsight it does provide a significant date by which to identify, some 11 years on at time of writing, a time to close up shop properly and finally and hand-over the legacy, including this brief history with some anecdotal insights that would otherwise be lost. Those of us involved and our institutions and associations are delighted with and indebted to Designing Buildings Wiki for taking this on.

At the time of the cessation of activity of CPIc the membership comprised representation (1 officer and 1 member) from the following sponsoring bodies:

- The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) – also held the chair role as additional

- The Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS)

- Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE)

- The Chartered Institute of Architectural Technologists (CIAT)

- The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE)

- The Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB)

- The UK Contractors Group (UKCG)

- The Landscape Institute (LI)

also

- 2 Co-opted Experts

- 1 Technical Consultant (on computing matters)

CPIc Prehistory >1979 – the need for clarity, coordination, consistency, punctuality, precision …...

“A working drawing is a letter to a builder telling precisely what to build, not a picture to charm the client” Architect Edwin Lutyens about 100 years previously.

Anecdotal and observed serious shortcomings with construction project information had been recognised for years but for formality we shall identify the start of the CPIc prehistory as the point at which the years of concerns finally attracted specific and allocated central government funding for a focused attempt to rectify them. It therefore starts with PIG, the memorable, short version acronym of the Project Information Group of the National Consultative Council Standing Committee on Computing and Data Coordination in the Construction Industry – so you can see why the report in which its findings are presented is generally called ‘the PIG report’.

The PIG report stated in 1978:

|

1.1 Reports over the years have pointed to the benefit which improved communication in the building industry can bring. Evidence that such improvements in project documents are needed can plainly be seen from an analysis of the amount of site queries which result from information prepared for communication from designers to site which is: Work by the Building Research Establishment (BRE) [1] has shown that a high proportion of site supervision time is spent in sorting out technical problems due to unreliable and incomplete information; this can result in the site staff becoming frustrated and a consequent reduction in the quality of the work and a general disinterest in the project. 1.2 Better project documentation would bring other benefits. A clearer method of arranging drawn information would bring about more efficient working between members of the design teams and enable more positive communication with the client. By providing the contractor with project documents subject to less of the deficiencies in (a) to (e) above, the designers and quantity surveyors would find themselves freed of many of the time consuming disruptions whilst errors and omissions were dealt with. 1.3 Finally, claims and variations cannot be regarded as symbols of an efficient industry. While some are caused by factors outside the construction industry's control, for example clients' changes of mind, the present level of claims has in no small measure resulted from inadequate or unreliable project information, particularly at the tender stage. Improvement in project information can only lead to a reversal of the trend to set up claims organisations. We feel that some positive means should be found to reduce the amount of claims being made by contractors. |

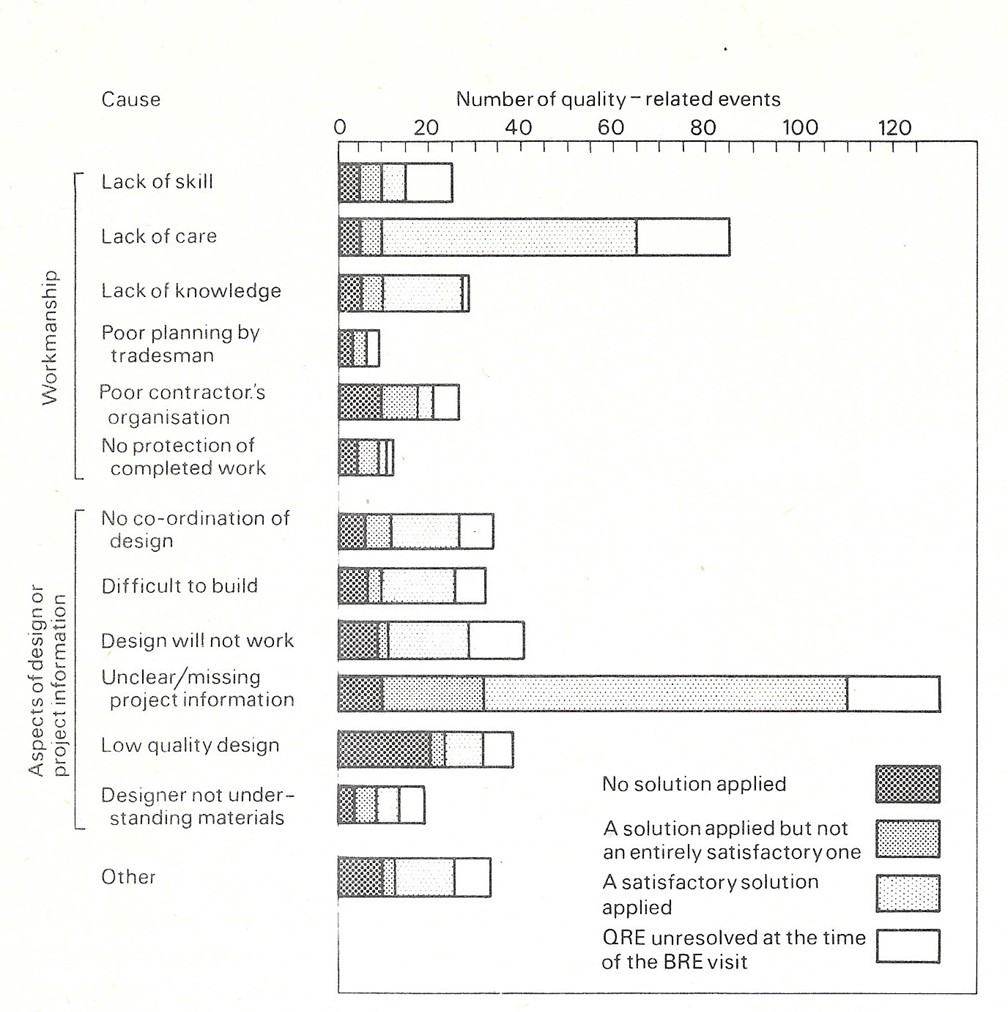

Other BRE research at about the same time came up with startling data, particularly taking account of the objective veracity of its collection methods. The work was not referenced by PIG as it was a separate and independent study, into achieving quality, that was still on-going. At its start it had no preconceived ideas of what may be found and was based entirely on observations from full-time observers [2] blended into the backdrop of normal site activities for lengthy periods so as not to affect any outcome while they passively followed the resolution of what became called ‘quality related events’. The first results from the quality work were published in 1981 by BRE as Current Paper CP 7/81 [3], read mostly, one presumes being a BRE paper, by those from the sector. Later, after a second phase targeting a wider range of procurement methods and client types the full work was published by government (by the then National Economic Development Office). The NEDO paper “Achieving Quality on Building Sites” targeted influential readership of business leaders that used the services of the sector as well as those from the sector itself – effectively clients and mostly knowledgeable repeat clients.

That research showed that for all quality problems studied real time on sites over a 7 year period, by far the largest proportion were caused by missing or inadequate project information. Furthermore, when serious quality problems (defined as potential severe compromise to the integrity of the construction) were separated out, whilst not quite so dramatically larger than all other causes, it still was the largest by a significant amount.

This very specific, objective, rigorous and lengthy research confirmed and quantified the trends shown from many earlier studies of the role that unclear information played in the poor performance. It is included here as it is the most graphic illustration of the problem previously expressed in the anecdotal words from the Lutyens quote and in the more general statements from many independent reports on the performance of the construction sector such as the ‘Banwell Report’ 1964 and ‘Tavistock report’ 1966. Later, the ‘Latham report’ 1994 and ‘Egan report’ 1998 both cited the lack of collaborative working as continuing to cause issues and both also recommending the use of the CPI conventions with Latham proposing that they be made mandatory, which of course did not happen.

| Anecdote: Contrary to much of the rhetoric of the sector quality was mostly lost not through lack of knowledge or skill in individuals but characterised by lack of care. In the case of the information for example – quite often the necessary information existed but through careless (frankly ‘sloppy’) processes, very often it was not incorporated in the production information and no one, sometimes even the originator could find it when it was needed. At best this caused delay and cost and, on occasion, more serious issues. The report stated that the biggest influence any participants can have in preserving quality, whether it be for example the state of the information or the state of the site facilities, was to “create an environment in which it was likely to happen”. Skill and knowledge shortages (availability of skilled people) should not be confused with the skill and knowledge within trained people. They are very different things. Matters of ‘lack of care’ are overwhelmingly organisational and management issues not those of individual professionals or operatives – the ‘environment’ in which they work. |

Even without specific reference to this separate ‘quality work’, as it became known, the government fully backed the PIG recommendations which included the setting up of a representational group to prepare guidance and codes of practice. As well as cash funding, the government support included significant effort in kind from the (then) fully funded Building Research Establishment which already had significant expertise in the subject and good relationships with the representational bodies within the sector.

Lutyens’ language was of its time and as such only cited drawings but the PIG report defined project information formally as:

| "that information concerning a specific building project (e.g. the survey of the site, the proposed design solution and the information required to carry out the construction phase) which passes between members of the design team and other bodies, in particular the client, statutory bodies and contractors. It does not include General Information (e.g. byelaws, regulations, manufacturers' catalogues etc)" common to many projects" NB Later, in the detailed work, it became clear that there could be some confusion between pre and post tender Project information so the term ‘Production information’ to describe post contract was also used. Also that it was independent of contractual relationships and so reached beyond the classical definition of ‘the professional design team’ to include contractor and specialist design. |

The PIG report was comprehensive in its analysis of the issues and definitive in its recommendation.

It broadly identified:

- Drawings

- Specifications

- Measured quantities (Bill of Quantities)

As the existing documents causing the majority of problems with coordination and consistency between them as a major issue so it addressed this also as requiring a:

- Coordination framework

Whilst there were some inconsistencies in the use of terms such as ‘guidance’, ‘recommendations’ and ‘codes’, PIG recommended the undertaking of work on each of these and of an oversight to bring it all together holistically with a view to creating definitive, and of course coordinated, guidance involving both new documents and, if necessary, revisions to existing publications to ensure alignment.

The PIG report did not shy away in its commentary from the issue of professional fees, schedules of services and engagement contracts either. All of these can have a significant effect on coordinating information from disparate sources and the report pointed out that any additional costs in alignment across disciplines would be comfortably compensated by greater overall efficiency. However, it left this issue for the professional institutions to remedy and so, having placed this aspect outside the post-PIG ring-fence, predictably, nothing happened. This was in the period up to 1985 and the Building Industry Council was not formed until 1987 and became the Construction Industry Council (CIC) in 1990. CIC subsequently attempted to address aspects of this issue many years later but with only limited success in terms of take-up of the CIC Consultants Contract Conditions (~2012).

| Anecdote: Not that fee structures were being ignored. After having its ‘mandatory fee scales’ outlawed as unfair by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission in 1982 following a three year investigation, the early 90s saw the RIBA once again tussling with government (by then the Competition Commission), this time over the notion that its retitling the scales as ‘recommended’, rather than the outlawed ‘mandatory’, legitimately answered the accusation of price fixing, notwithstanding having ‘got away with it’ for ~10 years. The argument was lost by the RIBA and subsequently the scales were significantly recast and a document titled ‘Guidance for clients on fees’ was issued in 1994. Guidance on calculating fees (how to, not how much) was also prepared for RIBA members. With management issues being found be so influential to the eventual quality of construction projects (the BRE ‘quality work), this guidance drew on Chapter 7 of the 1987 CPI ‘Drawings code’ which covered working out the resources involved in ‘Planning, preparing and issuing the drawing set’. |

From prehistory to history

The PIG report recommended work-streams, some new and some already started, to come together:

| “In order to ensure that these pieces of work do not diverge from one another, there is a need for a Group representing the major institutions to meet at intervals to monitor progress on new developments and to ensure that co-ordination is continuing. There is advantage in the Group having much the same membership as our own so that the knowledge which has been gained so far in this Group would not be lost.” |

This group was made up of representational bodies and was called the Co-ordinating Committee for Project Information and CCPI became the first of the acronyms in our formal history and it made a start in supervising the work-streams at the BRE and elsewhere. CCPI first met in 1979 and at the BRE and through other contracts, such as with the National Building Specification (NBS), Design Office Consortium (DOC - later to become the Construction Industry Computing Association - CICA) and the Building Services Research and Information Association (BSRIA), resources were deployed and work began in earnest. The objectives of this work was to produce authoritative guidance and whilst there was some further discussion about what this should be, the form it should take and what the various titles might be, from very early on the vision was agreed and remained consistent and as they were eventually published in 1987.

| Anecdote: In 1979 computing and Computer Aided Drafting (CAD) in particular was very much on the horizon and the research recognised this early on. BRE engaged Design Office Consortium (DOC) later to become the Construction Industry Computing Association (CICA) to test some CAD systems with drawing exercises, one of which was an in-situ pre cast concrete circular staircase. The results were disappointing with none able to adequately perform the tasks within the time allowed on day 1. The burning of midnight oil was evident however in that all could do it and demonstrate the results albeit with varying degrees of success by the next day. The general conclusion from this, other tests and discussion was that at that time (and revisited in the year prior to publication) the use of CAD was a little ‘over the horizon’ rather than ‘on it’, particularly bearing in mind that the objective of the entire exercise was, mostly by studying in depth real projects: to document, rationalise and codify the best practice of the time to provide for the rest to be able to come up to that level. It was not to push beyond that at the top. By publication in 1987 the technicalities were less of a barrier but cost and take-up still made CAD use relatively rare and certainly not routine. |

The research was mostly focused on what was generally agreed, by the representational bodies and previous research, to be the “best of current practice” and the objective was to establish ‘codes’ whereby the bulk of the sector could aspire to these proven practices. It was not intended to push the frontier of practice into new and particularly not into untested territory. However there was recognition that by being the summation of best practice even those currently seen as ‘good’ may still learn and so improve. Thoughts of recession naturally tend to go to the most recent but it must be remembered that these were recessionary times with interest rates at ~14% and a powerful argument was that those consistently working in thorough and responsible ways and staying in business were a legitimate example for all.

| Anecdote: For the research in the earlier 1970s BRE work the approach was taken in establishing a research sample to ask the professional bodies such as the RIBA “who among your members produces the best production information?”. For the new CCPI funded research from 1979, a fundamentally different approach was added and that was to also ask the receivers of information, such as co-consultants and constructors, “from whom do you receive the best production information?”. There was some cross-over between the two lists but they were different. The names of those chosen and agreeing to take part became known - but not which list they came from. Otherwise the lists were, and remained, confidential known only to the researchers but with all kinds of, usually light hearted, guessing sometimes going on at CCPI meetings. In all seriousness however it was one factor that led to the confidence in the findings and in the eventual codes. |

Three work-streams directly under CCPI were established for: Drawings, Specification and a framework for Work Sections and a fourth with a coordinating role between CCPI and the work being undertaken by the NFBTE and RICS on the organisation and rules for the Standard Method of Measurement. Between the participants and especially the researchers this distinction did not impinge on the ‘one team’ feeling in the work. Steering groups for each work stream and the coordination were established with some cross population from among the appointed representatives. The chairs of these along with other appointed representatives met as the main Coordinating Committee. Lead research organisations were appointed for each work stream again with cross population of researchers involved and of course an obligation to collaborate as work proceeded. The lead organisations engaged others as necessary to provide comprehensive expertise coverage.

Overview of the research:

Complete sets of production information (Drawings/Spec/Bills) were obtained for real projects that were mostly on site at the time and at a mature stage. Later testing of proposed guidance involved early-stage projects. Most of the research used the ‘workpiece technique’ largely at BRE’s offices, but with some at BSRIA, interrogating the documentation under the headings of ‘search’ and ‘content’ to establish the steps for the information for ‘work-pieces’ to be found and how complete was its content once found, noting questions and ambiguities thrown up along the way.

A rule of referencing (referencing systems in general) is that it should go from the general to the particular, so each search had an origin of a very general nature from which point searches proceeded and noted after indicating ‘O’ for Origin in descending usefulness as:

| R | Reference | a direct reference was provided that led straight to required information |

| 1 | Strong clue | a strong indication led fairly quickly to or close to the next piece of information |

| 2 | Weak clue | a weak indication led after some time to or fairly close to the next piece of information |

| 3 | Element code | a code e.g., SfB [4] element code (21) say, for external walls led generally to the next piece of information (a code but with more specificities was usually a part of a direct reference) |

| 4 | Whole set | there were no clues to aid the search |

NB In a well titled set, using drawing titles from the register was generally classified as a ‘weak clue’ but if the titles were very poor then they might be classified as ‘whole set’.

The weaker the search, even if it seemed to eventually satisfy the content need, left the question “is there something else relevant but not evident?”

Searching stopped when either all the information to build the designated workpiece was found or where the search had found that further information was not available or definitive. A designated work piece might be for example:

“To find the information necessary for construction of the slab and edge beam on grid 22 between grids W and X”

Each workpiece analysis was then shared with co researchers and assessed, with that assessment recorded to provide the input to the research data. Randomly selected samples of this data were also checked back with the sites from which the information came but only after that work on site had been completed for some time. This also gave insight to any subsequent requests for information that had occurred on site and any elaboration of the formal information used on site – e.g. sketches or notes from the manager to the operative(s) and notes of any delays or disruption caused by errors, contradictions or ambiguities.

Particularly for dimensions there were frequently contradictions between information from various discipline sources such as structural engineers and architects. The use of grids helped but where a discrepancy involved the grid itself the consequences were usually more serious.

| Anecdote: Although no specific guidance eventually appeared in the published codes it was noted in the research that the use of grids, particularly at later stages when interiors of the building were becoming increasingly sub divided and sight-lines obstructed, could cause difficulties particularly when combined with issues of tolerances and fit (as defined the British Standard BS 5606:1978). Recreating grids on the site was often relatively cumbersome at least, and often frankly difficult to do accurately when compared to the visual or functional need, for example, for elements to align. A column surface and partition, whilst both within permitted tolerance could, if each were set out to dimensions from grid lines – which many drawings indicated – could show a significant, but apparently permissible, step of several millimetres at their intersection. This was covered in principle in a later edition of BS 5606 but the research showed that it caused annoyance and sometimes slight disruption with the ‘common sense’ approach, mostly not sanction by an instruction as to which carried president, generally prevailed. |

For assessing specifications specifically, the first exercise was to separate those that had specification information only, relating to the production information and those where specification information was included in the billed items and so probably not updated from tender stage except by cross referencing site or contract instructions. Established from previous research and confirmed emphatically through the rigour of the desk studies for the CCPI work, one of the fundamental principles was that to function effectively ‘specification’ for production information is first a verb and that specifying is a design not a measurement activity so specifications for production purposes have to be prepared by designers during the design process and updated with the same rigour and control as drawings. This, however, contradicted massive but largely unrecognised bad practice that was rife within the sector and only exacerbated by the evolution of procurement developments where much specification attached to Bills of Quantity were the guesswork of a quantity surveyor in order to allow the tendering contractors something to price within a timescale when detailed design was still developing. There were complex and agreed ways of dealing with these tacitly acknowledged and often expected measurement discrepancies through the periodic (usually monthly) valuation and remeasurement exercises during construction however. The discrepancies were often accepted as a matter of fact even when recognised as clearly both inefficient and open to error and abuse. Moreover it still left contradictions of technical specification matters as specification documents had invariably not kept up with developments in the designs and expressed primarily through the drawings. Valuation exercises were primarily about keeping the money accurately accounted for, but being largely after the event, errors due to technical discrepancies would have already happened and the valuations were simply incorporating the cost of these, including the time and cost of any arguments about responsibility for the errors. Separating specification from bills and keeping it a design responsibility including updating was a starting point for establishing good practice.

Beyond that, whether separate or combined with the Bills of Quantity (but especially in the latter case) these documents abounded also in indirect and obscure language rather than being clear, direct instruction (remember the Lutyens quote) and there was a very poor understanding of matters such as specifying by reference or prescription, alarmingly including the legal liability implication of each, and when each, including combined, was appropriate.

| Anecdote: There were contracts at the time, particularly those referred to as “fast track” where there were no Bills of Quantity issued specific for the project but where schedules of rates only were prepared against which tendering contractors would submit prices to compete in the tender process. Once selected and with more information available a contract price was reached through negotiation. Although not common this was a well known technique often favoured by very experienced and serial customers of the sector. A fact which may have some significance in the light of the vagaries of the traditional system where Bills and their relationship to the reality of the eventual design were often not much more than an imprecise vehicle to provide similar indicative rates for the valuation and remeasurement processes to sort out also giving rise to extensive claims involving both time and money. |

A specific framework for tying all the documentation together was clearly needed. Several examples existed but few were used expressly or consistently particularly in respect of references from drawings to specifications. The most common presentation within drawing sets and between drawings and specification presented the majority of searches as the ‘clues’ noted previously and many required searching the whole set. Even within the study samples recommended as good there were some that had little system to them. In the best performing sets there was a clear indication of the discipline of origin, for each of those a distinction between the type of information (e.g. location, assembly or component information) and subject of construction (e.g. ‘external walls’).

- Discipline – e.g. Architect

- Type of information – e.g. Location, Assembly or Component

- Subject of construction (Element) e.g. using the CI/SfB element code such as (21) for external walls

- A unique sequential number

So the number A/A(21)02 would indicate the Architects set / an Assembly drawing about (external walls) and the second drawing in that subset.

|

Anecdote: Linguistics and logic vs custom and practice …. one lost battle. As noted the favoured ‘type of information’ breakdown for providing drawn information to aid searches was: Location /L – where the various components assemblies and parts are located Assembly /A– the detailed information of how to assemble parts of the building from materials (such as bricks, mortar etc), or from components (such as windows or door-sets etc) Component /C– how to make and install the components - often factory made and proprietary. Schedules /S– being so different in their presentation were often a fourth ‘type of information’ but in reality provided location information and references to the necessary detail so were sometimes given /L numbers. These terms tell what the purpose of the drawing is and aid searches that go from the broad L (S) to the particular A and then C. However by the time the updated codes were prepared (2003), sector pressure, including from the USA with CAD systems and surprisingly less rigour with semantics, for the (linguistically troublesome term) General Arrangement or GA’s to reluctantly be reintroduced as an ‘acceptable’ option, albeit not preferred. Linguistically “General Arrangement” says ‘well it is generally like this ….. but don’t go looking for anything definitive, precise or accurate’ whereas “Location” says ‘it is here ….. exactly’. Similar compromises were not made over other ‘military rank’ vague and troublesome terms such as “major revisions”. Revisions, even if ‘minor’, must be accurately described and positively identified/located not just vaguely referred to as if in a ‘spot the difference’ quiz. |

In the sector, and even within the ‘good examples’ provided for the research where inevitably some performed better than others, there was a tendency for the consultant team, having confidence that the information was provided, to not see the benefit of making it easy to find. There are legitimate arguments related to the size and or complexity of the project and it follows that the larger or more complex (or simply more information need for any purpose) benefited more from sophisticated search aids such as the L A C system and element codes. From the start of the research a model was created that showed this complexity plotted against the axes of benefit accrued and level of complexity (see appendix 1 and the section: “Production Drawings - A code of procedure for building works”). One strong matter of guidance was therefore that the producers of the information should always explain how the system used on any particular project operated as a part of the issue process and that information registers should be rigorously updated indicating as a minimum the purpose, issue date and currency of each item described by its title and number.

A Common Arrangement

Imagine yourself in 1980 or so, as a leading construction contractor or leading trade or specialist contractor or maybe a fairly small specialist or trade contractor with a good reputation with your trade organisation. Following recommendation for the research by your trade body, a researcher (an experienced professional) would make an appointment to interview you, preferably with some key operational staff, and ask some structured questions, around each of which focused conversations would ensue.

Put simply the questions were (in no particular order and sometimes circling back):

- What do you do? (could be multiple – if so proceed for each one as below)

- What do you call what you do?

- What does what you do involve?

- Where in the overall process does what you do start? (including details of acceptable presentation of workplace, completion of preceding activities/trades etc.)

- Where in the overall process does what you do finish? (including details of how you leave your work for following activities/trades etc.)

- What other activities are adjacent in the overall process to yours but you do not do – and what are they called?

- From whom contractually do you take your instructions?

| Anecdote: One specialist piling contractor respondent to the above had a good quip, certainly memorable, that both typified the worst and the best of the sector (and maybe the early 80s economic climate). He ruefully said: “If you pay me enough I’ll paint the walls too”. |

If the responses to all the interviews were plotted as circles there would be a myriad of overlaps and some gaps; a pretty accurate picture of the sector. Analysis, some follow-ups to sense check and some rationalisation created the basis for work section content and boundaries at a fine enough level such that there were no overlaps or gaps for conventional construction operations. CAWS was, therefore, a view of contemporary working practices at the finest practical level matching real world activity, and at this level produced around 300 ‘work sections’ collected into sub groups (around 110) and groups (around 25). In any actual project a single contractor may take on one or many (for example many types of roofing within the “Slate/Tile cladding covering” sub group but in each case they could be packaged, for example for sub-contracting purposes, with relatively hard boundaries.

In terms of measurement the SMM Development Unit (RICS and NFBTE) was an established group and had not long since updated SMM5 to SMM6. Whilst SMM7 was to be a radical step forward in arrangement, layout and language much of the technical content of the rules had been thoroughly discussed including research undertaken by the University of Reading College of Estate Management. Not all of Reading’s recommendations had been implemented however. This was in part as SMM6 was identified as a likely short lived update acknowledging that the work of the PIG was then underway and what was to become a more holistic look at all project information (to become the CPI work) was predicted and anticipated.

There were two main strands: recasting and re-writing the measurement rules which meant participating in the work on CAWS which was to be used for this purpose, and preparing guidance for what was seen by many as a radical new approach. The first produced a far more organised format with clearer language presented in a tabular layout and whilst having more sections to reflect modern practices, particularly in sub-contracting and using CAWS, actually a very much simpler logic allowing bill items to be built up consistently and realistically. The second was to create a guidance document that would sit with the other two guides (Drawings and Specification codes) and CAWS and which is visually similar barring the small CPI logo (indicating a ‘coordinated document’) instead of the large for copyright and other ownership reasons.

Whilst theoretically having a more mature starting point it was the final agreements on the documentation emanating from the work for SMM7 that held up eventual publication of the entire initial set of guidance for about a year.

Bringing the research together and presenting the results to the sector created the guidance documents which allowed project information to be logically compiled and used with each document referencing each other.

From CCPI to BPIc and CPIc – a time-line of publications and major events 1987

(See appendices 1 and 2 for more detail of the publications)

CCPI approved the research reports and recommendations in the period 1980-85 and signed off publication drafts at the end of 1986 and, apart from sanctioning a programme of implementation of the ‘codes’ in its own (PSA - Property Services Agency) design offices, this was also the end of direct government involvement. With seed funding of £16000 (£58k in 2024) from the sponsoring bodies the Building Project Information Committee (BPIc) was set up on 17 February 1987. The seed funding was covered and repaid in the first 9 months of operation with a further £32000 (£117k) of net income from sales accrued in the first 4 years resulting in BPIc redistributing a proportion back to each of the sponsoring bodies.

The initial sponsoring bodies were RIBA, RICS, BEC and ACE which represented both CIBSE and ICE. ACE [5] resigned in 1992 and engineering interests became represented by CIBSE and ICE. After the arrival of ICE the committee became the Construction Project Information Committee (CPIc) to better recognise the inclusion of civil engineering works as a part of construction and between then and the cessation of operations BEC was superseded by first the Construction Confederation and then the UK Contractors Group (though the representatives remained the same) and the Chartered Institute of Architectural Technologists (CIAT), the Chartered Institute of Building (CIOB) and the Landscape Institute (LI) also joined the committee.

Under more lengthy and detailed terms of reference the principal role of BPIc was to promote and maintain the initial publications and to respond to the need for further publications on the subject of project information with the aim of reducing disputes and improving the efficiency of the construction process.

The initial 1987 publications were:-

- Project Specification – A Code of Procedure for Building Works.

- Production Drawings – A Code of Procedure for Building Works.

- A Common Arrangement of Work Sections for Building Works.

- Co-ordinated Project Information – A Guide with examples.

and

- A 24 minute instructional video (VHS) presented in the most part by Professor Douglas Wise, Director of the post graduate Institute of Advanced Architectural Studies at the University of York from 1975 to 1992 but featuring other spokespeople and individuals from the research and from the sector.

Often seen as a part of the above and indeed following the presentation format and style but with separate copyright holders:

- The Standard Method of Measurement for Building Works – 7th Edition 1987

The principles set out in these publications were adopted in the preparation of the following services and documents:

- The National Building Specification (NBS)

- The National Engineering Specification (NES)

- The PSA General Specification

- The Library of Standard Descriptions (HMSO)

- BS 8000 – Code for Workmanship on Building Sites (BSI)

- OPUS – Building Services Engineering Products Directory

Various other services and documents followed.

In 1992 BPIc commissioned research from a separate part of BRE than that had previously been involved (and based, as it happened, from BRE’s Scottish Laboratory). There was limited funding and this caused a problem in the techniques available. The researchers used questionnaires and random samples and initially reported that take-up was relatively poor. When questioned by BPIc and advised – with limited extra funding - to try face-to-face “tell me/show me” techniques, the results from the “show me” produced significantly better results. The reason for this is that the guidance documents were not of themselves manuals as one might have in a QA system for example, but were used by the individuals responsible to create office handbooks or similar procedures. So, on the “show me” part of the exercise many sets of drawings and specifications for projects were seen to be, or very close to, following the CPI guides but what the people working on the projects were doing was following the practice manuals with no knowledge they were based on CPI. Poor PR for CPI but exactly the right result. There was also notable plagiarising of manuals and processes from large practices into smaller practices as staff moved on. Again maybe not particularly correct, but an excellent result for dissemination of the guidance. This was not interrogated or exposed at the time as ultimately this “trickle down” was deemed good for the sector and more importantly its clients. This work by BRE Scot Lab was kept internal to BPIc but did partly lead to the Case Study project.

In 1993, in response to the take-up research by BRE Scot-Lab and calls for fully worked examples, BPIc published ‘Production Drawings – A Case Study’ to illustrate how CPI documents had been used on a live, and as it happened, prominent project. Whilst very good, the example project was not perfect in its application of the CPI conventions but this was used to instructional advantage by illustrating some of the research techniques as developed for the original BRE evaluation techniques such that they could be used to audit the efficacy of information produced. It was hoped that use of these techniques might develop into an audit tool but that initiative was never realised. Indeed the format chosen to publish ‘Production Drawings – A Case Study’ A wallet with three booklets: 1 Description of the project and the study; 2 & 3 Fold-out copies (reduced) of the drawings referred to in the example searches; made the published document rather too expensive to attract the sales hoped for especially among students.

| Anecdote: The example project came from a large multidisciplinary design office that had featured in both lists noted in a previous anecdote and which had advanced internal processes and procedures that both preceded the Codes and very much influenced their content. Also they were a beta test partner to a large CAD software house and some of the discrepancies were due to the recent imposition of particular processes required for that. Indeed around this was one of the earliest debates over the ‘machine/human’ aspects that were to rumble on and particularly re-emerge 18 years later under the ‘UK BIM initiative’. The BPIc view at that time was that no compromises to the human processing of information should be made to accommodate technology limitations. |

1997 – Uniclass.

In 1991 £5,000 (£18000 in 2024) from income had been contributed towards the cost of a feasibility study on a Unified Classification for the sector which was subsequently developed into Uniclass. Uniclass was first published in 1997 and at the time of the cessation of CPIc was being developed as Uniclass2 in line with current practice including particularly the needs of BIM.

The first Uniclass was, in effect, a rationalised collection of 15 tables based on extant systems such that the tables therein could be used, separately or in combination, for;

- arranging libraries

- structuring product literature

- coordinating project information

- structuring technical and cost information

- developing frameworks for databases

It included the CPI CAWS tables amended and added-to and presented as “Table J Work sections for buildings” and “Table K Work sections for Civil Engineering works” and used both concise and full tables to apply to required levels of detail. It was based on ISO Technical Report 14177 Classification of information in the construction industry (1994) and also provided guidance on using the system.

In 2002 in a programme funded by the then Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) the CPI protocols were used in a mandated way on a series of projects. Otherwise they were all ‘ordinary’ building projects with a spread of building types, sizes and technologies. The projects were all fairly conventional, and used normal professional appointments, contractual arrangements, insurances, penalties etc. The programme was called Avanti – ICT enabled collaborative working, and the only difference compared to other projects of the time and within the offices of their consultants and contractors was that they were each facilitated by individual mentors who knew the ins and outs of the relevant protocols including some that were in draft at that time such as documentation that was to evolve into BS 1192:2007.

Avanti reported in 2007 and on average showed savings in line with those later expected in government ‘BIM initiative’ from 2011 -2016 of around 20 – 25%. Individual savings recorded for particular activities were even more startling:

- Early commitment offering up to 80% saving on implementation cost on medium size project

- 50-85% saving on effort spent receiving information and formatting for reuse

- 60-80% saving on effort spent finding information and documents

- 75-80% saving in effort to achieve design co-ordination

- 50% saving on time spent to assess tenders and award sub-contracts

- 50% saving on effort in sub-contractor design approval

| Anecdote: Another initiative of the time with a good patronage and a promising title "Building down Barriers – a Guide to Construction Best Practice" analysed the reasons for ‘initiative failures’ of the past and ironically also predicted its own failure in an early passage where it stated: “The reason why the numerous reports between 1929 and 1994 have failed to have any impact on the performance of the built environment sector is because the sector continues to be blind to its failings. It is also unwilling to measure its performance, particularly the impact of fragmentation and adversarial attitudes.” This proved true of Avanti too. |

Avanti was seen primarily as a research experiment – a glimpse of a possible future for those involved but it was ‘back to normal’ on the next and subsequent projects for most. Exposure to Avanti slightly swelled the ranks of those individuals convinced by the methods and committed to improvements but they were still very much in the minority and mostly then with very little influence in the face of hard rooted complacency in the sector.

In 2003 the new publication ‘Production Information: a code of procedure for the construction industry’ was produced. This superseded the previous publications, ‘Project Specification – A Code of Procedure for Building Works’ and ‘Production Drawings – A Code of Procedure for Building Works’ and drew on the early experiences of the Avanti project and the drafting of BS 1192. It also drew the specification code and drawings code into one publication which, with hindsight, made more sense, and also recognised the intervening take up of the use of Computer Aided Drafting (CAD).

The 2007 British Standard BS 1192:2007 drew heavily on and incorporates methods of working established in ‘Production Information: a code of procedure for the construction industry’ and refined in the Avanti project. This BS Code also recommends the use of Uniclass as the classification system for the sector.

In January 2009 an essay/thought piece by the then Director of Practice at the RIBA and also a CPIc representative, titled ‘Drawing Is Dead - Long Live Modelling’ set a case for the implementation of BIM. Only the introductory essay was made generally public but, in an annex and probably more importantly, it went on to openly challenge the sector under the participant headings:

- The professions and professional institutions

- Government, as an advisory body, as a regulator and as a procurer (client)

- Representative bodies such as CIC, Building Smart, BSI and CPIc itself

- Contracts writing bodies such as JCT (Joint Contracts Tribunal)

- Insurers

- Software vendors

- and ‘Others’

to support (and further develop as necessary) a definition for BIM and undertake enabling work as suggested in the text for each participant. It even provocatively attached an endorsement sheet and the full paper was sent to those thought most appropriate to respond and particularly those represented in the list above. A couple of institutions in fact did endorse the paper!

Interestingly in 2011 the government hypothesis about BIM included: “Government as a client can derive significant improvements in cost, value and carbon performance through the use of open shareable asset information” [6] and launched its ‘BIM initiative’, funded until 2016.

Anticipating the emergence of BIM as the hot topic, in 2010 with the support of CPIc a co-opted CPIc member collaborated with BSI and created a guide to BS1192:2007. Publication of the document “Building Information Management – A Standard framework and Guide to BS1192 (2007)” was from BSI rather than CPIc but with both acknowledged on the cover and within. Writing a national standard is a very disciplined process and the language used quite particular. BS1192[7] was a Code of Practice and as such states requirements against which compliance may be measured and in writing a Code it is sometimes difficult to “be helpful” with guidance. Against this background and answering calls within the sector, the BSI/CPIc document works through the processes elaborating and exemplifying with copious diagrams, illustrations and references back to the Avanti project and other observed good practice.

CPIx - Construction Project Information Xchange

In 2009 as a development of a project (PIX – Project Information eXchange) instigated by the Building Centre Trust and with further input from construction contractor Skanska, CPIc and in consultation with the government BIM Task Group, CPIc published beta versions of the “CPIx BIM strategy templates” that complied with the requirements of the developing new version of BS 1192 (PAS 1192-2)

They comprised downloadable templates under the title of the CPIx Protocol:

- CPIx BIM Execution Plan

- CPIx BIM Assessment Form

- CPIx Supplier IT assessment form

- CPIx Resource Assessment Form

For some time after 2013 by which time other work had ceased, maintenance of the templates remained the only legacy activity of CPIc and they were eventually taken over by BIM UK and remain available.

Work on Uniclass 2 came to (virtual) fruition under a contract between NBS and CPIc in 2012. Uniclass 2 was significantly different from Uniclass(1) within which most of the tables had been familiar in the sector albeit not all or in every part. Uniclass 2 aspired to be a true classification system (rather than a linked collection of existing, albeit modified, tables) and necessarily used both very precise terminology that was less familiar and numbering that was less (human) memorable or recognisable but far more suitable for computing purposes. Whilst in its creation the process and tables attracted much discussion, deliberation and comment, under the name ‘Uniclass 2’ it had little penetration in the sector and fell foul of the period of the demise of CPIc activity and rise of other interests able to respond more expeditiously to the demands of the government ‘BIM initiative’ (2011 -2016 funded). Under that initiative and with funding provided by government, and by then out with the input of CPIc, Uniclass 2 morphed into Uniclass 2015 following further development but no conceptual change. CPIc had provided the foundation for the system now adopted and operated by the NBS.

Epilogue

The promotional video prepared for the launch of the first CPI documents in 1987 amusingly starts with the well known anecdote of the message from the war trenches being corrupted down the line of messengers: At the battle front the message clearly starts “send reinforcements – we’re going to advance” and through various stages of miss-hearing and interpretation it arrives at battalion HQ as “sent three and fourpence (three shillings and four pence) we are going to a dance”. It very neatly sums up the problems CPI was trying to address – and explains the title of this brief history.

The history of CPI from its inception up to the publication of BS1192 (2007) is an impressive catalogue of ‘firsts’. No-one kept count but in this time also, CPIc members, (and others versed in the subject,) delivered regular conference, CPD and educational lectures on the subject of project information. After that time the focus/title was usually on the British standards but of course that effectively meant the same messages and much reference to CPI. In its later years, up to the cessation of activity, CPIc had been a key player in alerting the sector and policy makers to such technologies as linked data, the use of ontologies and object oriented computer aided drafting leading to building information modelling (BIM) and highlighted that BIM would require the common approaches that CPIc had been promoting since 1987. However the veracity of the implementation under significant government funding from 2011 and with much of the intellectual property of CPIc available in publications in the public domain in any case, therein lay the beginning of the end of the story.

Encouraged by the funding being made available by government new initiatives emerged, some with support from certain CPIc sponsoring bodies which diverted further the resource available to CPIc. In May 2014 after much internal discussion, CPIc ceded its copyright in various original works and its ongoing development to the government which, through the then Technology and Strategy Board ran an open competition for consortia to submit proposals for completing the CPIc work on Uniclass and creating a pan sector ‘Digital Plan of Work’ (cf the well known RIBA Plan of Work). CPIc did not submit in its own right and continued to operate a legacy governance and a website for its publications and tools still in use. Albeit that certain of its initiatives took some time to be superseded and tools handed-over it received none of the new influx of funding and no new work was undertaken in CPIc’s name. Most of the individuals who had represented their institutions and associations on CPIc continued to contribute to the subject in other ways such as by serving on British Standards work. This brief history now provides the actual end.

Thank you.

References

- [1] Primarily "Working Drawings in Use" – Current Paper 18/73-a study of working drawings identifying the symptoms and causes of failure in communications between the producers of information and the site. Building Research Establishment 1973, but also others published and internal to government.

- [2] The observers were seasoned industry professionals but were not not ‘covert’ and if challenged readily said that they were from BRE and studying construction activities. Full management approvals (HQ and site) were always in place for their presence and by and large they did not overtly make copious notes in the presence of site staff or operatives. They passed the time of day but did not question directly and took time to blend-in so as to be almost unnoticed before making serious observations. It was difficult at times but to maintain the integrity of the research they did not interfere and on occasion had to watch mistakes work through. During the 7 years only twice was intervention deemed essential over issues of potential enduring safety and once over a massive dimensional error at foundation level.

- [3] And shorter information paper format BRE IP 28/81 under the title ‘Quality Control on Building Sites’ and this version was reproduced in Building magazine December 1981.

- [4] SfB stands for Samarbetskommitten for Byggnadsfragor, a Swedish committee that translates to ”The Cooperation Committee for Construction Issues”. It developed a tabular coding system and under license in 1968 the RIBA published a modified version called CI/SfB (Construction Index SfB) which included: Table 0 – Building Type such as “Education”, Table 1 – Elements such as “External wall”, Table 2/3 – Construction and Materials such as “Bricks” and Table 4 – Administration such as “Building Regulations” . Although used extensively and in full in product libraries, until the much later development of Uniclass the CPI interests in CI/SfB referenced only table 1.

- [5] RIBA – Royal Institute of British Architects, RICS – Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, BEC – Building Employer’s Confederation, ACE – Association of Consulting Engineers, CIBSE – Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers, ICE – Institution of Civil Engineers.

- [6] Main hypothesis of A Report for the Government Construction Client Group – BIM working strategy Client Group 2011

- [7] In 2018, it was confirmed that BS 1192 2007 (and the later PAS 1192-2) would be replaced by international standard BS EN ISO 19650 which was essentially based on and developed from the existing suite of UK BIM standards and introduced in 2019.

- “Bricks” and Table 4 – Administration such as “Building Regulations” . Although used extensively and in full in product libraries, until the much later development of Uniclass the CPI interests in CI/SfB referenced only table 1.

Related articles on Designing Buildings

Featured articles and news

ECA Blueprint for Electrification

The 'mosaic of interconnected challenges' and how to deliver the UK’s Transition to Clean Power.

Grenfell Tower Principal Contractor Award notice

Tower repair and maintenance contractor announced as demolition contractor.

Passivhaus social homes benefit from heat pump service

Sixteen new homes designed and built to achieve Passivhaus constructed in Dumfries & Galloway.

CABE Publishes Results of 2025 Building Control Survey

Concern over lack of understanding of how roles have changed since the introduction of the BSA 2022.

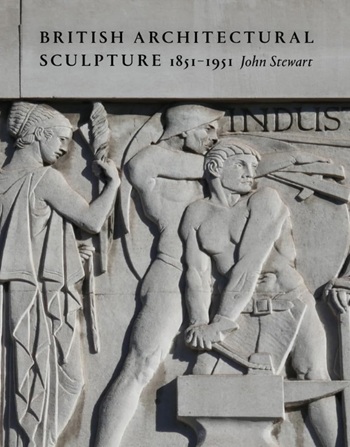

British Architectural Sculpture 1851-1951

A rich heritage of decorative and figurative sculpture. Book review.

A programme to tackle the lack of diversity.

Independent Building Control review panel

Five members of the newly established, Grenfell Tower Inquiry recommended, panel appointed.

Welsh Recharging Electrical Skills Charter progresses

ECA progressing on the ‘asks’ of the Recharging Electrical Skills Charter at the Senedd in Wales.

A brief history from 1890s to 2020s.

CIOB and CORBON combine forces

To elevate professional standards in Nigeria’s construction industry.

Amendment to the GB Energy Bill welcomed by ECA

Move prevents nationally-owned energy company from investing in solar panels produced by modern slavery.

Gregor Harvie argues that AI is state-sanctioned theft of IP.

Heat pumps, vehicle chargers and heating appliances must be sold with smart functionality.

Experimental AI housing target help for councils

Experimental AI could help councils meet housing targets by digitising records.

New-style degrees set for reformed ARB accreditation

Following the ARB Tomorrow's Architects competency outcomes for Architects.

BSRIA Occupant Wellbeing survey BOW

Occupant satisfaction and wellbeing tool inc. physical environment, indoor facilities, functionality and accessibility.